- Home

-

Products

- Frequency Converter

-

General-Purpose Inverter

FST-650L High performance vector universal frequency converter

High performance vector, low speed high torque output, rich and powerful functions, stable performance

Learn More + - Dedicated frequency converter

-

Inverter Cabinet OEM

Water pump dedicated frequency converter all-in-one machine

To meet the personalized and industry-specific needs of customers, it adopts a frequency conversion energy-saving control integrated cabinet mode

Learn More + - Drive Peripheral

-

HMI Display Screen

HMI display screen

HMI display screens are a key bridge connecting OT and IT information in the industrial field, making factory production management clearer and more transparent, and making equipment services more timely and efficient!

Learn More + -

Soft Starter

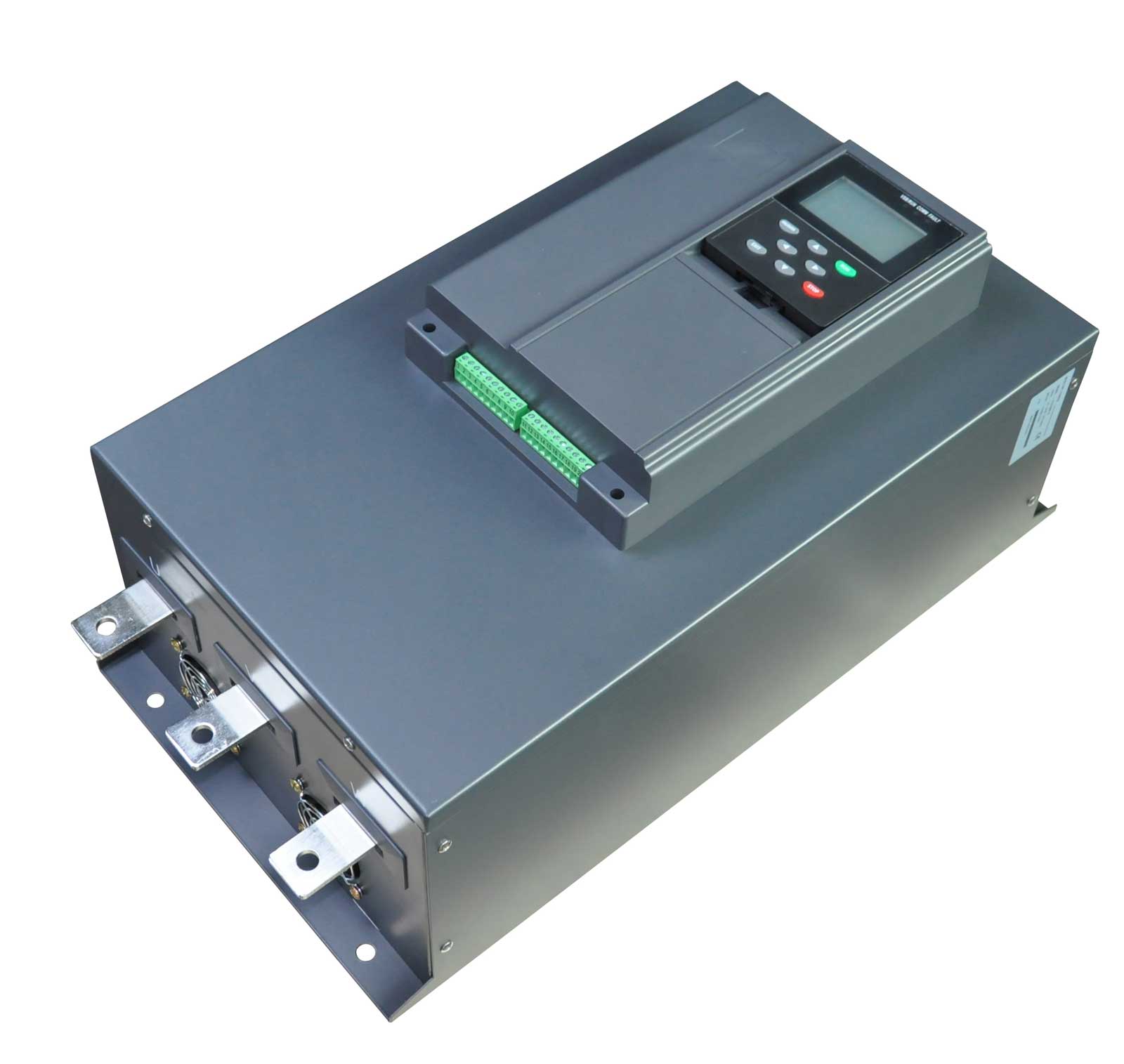

FST-3000 series built-in bypass soft starter

The new generation of built-in bypass multifunctional intelligent soft starter has strong anti-interference performance, complete protection functions, as well as multiple control modes and support for remote communication protocols

Learn More + -

Drive braking

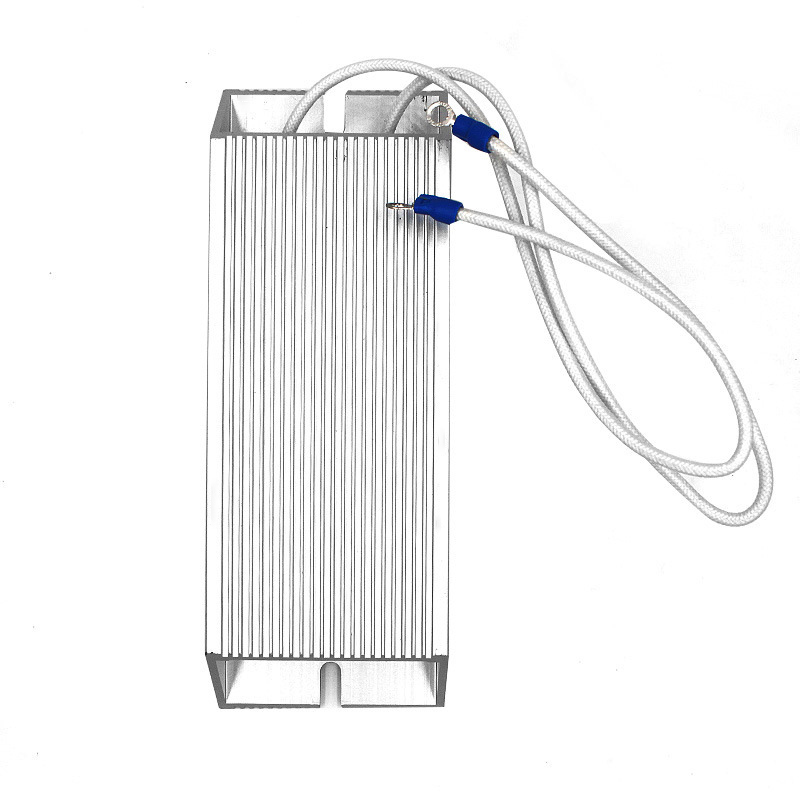

Fixde Resistors

Elevator brake resistor, frequency converter brake resistor, servo resistor, aging resistor, braking unit resistor, driving resistor

Learn More + -

Wave Filter

FST series input/output filters

Effectively suppress conducted interference propagating along power lines and reduce radio frequency interference generated by electronic devices

Learn More +

- Industry application

- About Us

- Service and Support

- Contact Us

Contact Us

Contact Us